Why I Research

In a recent LA Times Op-Ed Naomi Riley bemoaned academic research in the California State University system. The CSU, she argued, is a “teaching university;” why is the CSU faculty engaAging in research? According to her description full-time faculty avoid teaching by shifting the burden to lecturer faculty so that pre-tenure and more senior faculty can engage in research. Research is the mission of the University of California system, she argues, not the mission of the CSU. In conclusion she scolded CSU faculty, “get back to teaching.”

Ms. Riley’s essay suggests that only faculty benefit from research, earning tenure and promotion for their efforts. The fact is, students benefit from faculty who are actively engaged in research.

There is an old saying: “Those who can do, those who can’t teach.” The implication is that if we were any good at what we do we would be doing it rather than teaching it. Research is all aboutdoing; and doing research makes me a better teacher.

One of the courses that I teach is called “research methods.” In that course students learn how to engage in the systematic analysis of political questions. For instance, we might want to understand why some people vote while others do not. In this course students develop the ability to construct evidence-based explanations, engage in quantitative analysis of real world data, and consider how policy solutions might change individual behaviors.

How can I teach students to do research if I do not do research myself? Would you hire a personal trainer who did not keep himself in shape? Would you hire a plumber who did not fix your plumbing problem but only told you how you might fix it yourself? Probably not. So would you want to learn research methods from someone who does not engage in research? I certainly would not.

In my other courses I bring the fruits of my research directly into the classroom. Rather than parrot the textbook by teaching students what others have learned, I bring cutting-edge research on political institutions directly to my students, including the several hundred students to whom I teach Introduction to American Politics every year.

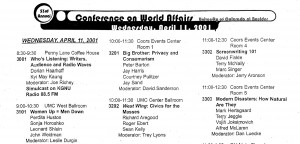

Some of my undergraduate students become directly involved in my research. Using data collected by me and my coauthor they gain hands-on experience pursuing a research project from beginning to end, and they present that research at student research conferences in California. Undergraduate research allows students to apply the knowledge and skills learned through their coursework to complex substantive political questions. Presenting at conferences allow them to gain experience in public speaking, increase their confidence, and help them to build a resume.

Some criticize us for producing students who are “book smart” but do not know how to apply their knowledge and skills. Undergraduate research unites the abstract and the applied and better prepares students for the workforce.

Many of my undergraduate research students are first generation college students (like me) who, perhaps, never considered the value of pursuing graduate work much less pursuing a job in higher education. Are these educational experiences that should be reserved for students who attend the elite University of California schools, prominent private schools like the Claremont Graduate University, or Ivy League schools? Do students who attend a CSU campus not deserve these opportunities? If I did not engage in research these opportunities would not be available to my students.

There are several other indirect ways that my research benefits my students.

Research helps me to build networks inside the real world of politics. These networks benefit our students. One of my standard research tools is “the interview.” By talking with politicians, political staff, lobbyists, and others involved in politics I gain insight into the practice of politics, and that benefits my research. But I also establish relationships with my “subjects.” By capitalizing on these relationships I am able to help students get internships that can lead to employment either directly, as the internship turns into full time work, or indirectly as the experience gained on the job makes the student more attractive to another employer.

Research helps me to build networks in academia. These networks benefit our students. Many of our students decide to pursue graduate education. They need letters of recommendation. Not all recommendations are equal. A letter that comes from a faculty member who has a “reputation” in the field carries more weight than a letter from an anonymous faculty member. Writing articles and books, and attending professional conferences to present my research improves my profile, connecting me with faculty from across the country. Sometimes a personal email or phone call to a faculty member that I know at their “first choice” graduate institution will get their application closer consideration, or an improved financial aid offer.

Faculty who are engaged in research are better teachers, better advocates for their students, and improve the reputation of the CSU system and their individual campuses. Ms. Riley does not fully appreciate that there is not a “strict wall of separation” between teaching and research. Teaching and research complement one another.

It does not surprise me that someone who has seemingly no sustained experience in college-level teaching or systematic research does not appreciate the relationship between the teaching and research. The implied accusation that CSU faculty are shortchanging their students by engaging in research is scurrilous at worst and unintentionally harmful at best. Discouraging faculty research in the CSU risks ghettoizing a CSU education; I will not be a party to that because our CSU students deserve the same quality education offered at the UCs and other more “prestigious” campuses throughout the country.