IRLC Update: Researching Mexican mobility

Rosalba Rocha participated in the 2015 Interdisciplinary Research Learning Community. In this piece from CI’s Channel Magazine, she discusses her research with Professor Luis Sánchez.

By Rosalba Rocha, ’16 Sociology

Last year I was given the opportunity to work on research with Assistant Professor of Sociology Luis A. Sanchez. My research project examines social and economic outcomes among the Mexican population in two border cities, San Diego, California, and El Paso, Texas, utilizing data from the 2012 American Community Survey.

Last year I was given the opportunity to work on research with Assistant Professor of Sociology Luis A. Sanchez. My research project examines social and economic outcomes among the Mexican population in two border cities, San Diego, California, and El Paso, Texas, utilizing data from the 2012 American Community Survey.

In particular, I was interested in studying social mobility across the immigrant and native-born population as predicated by the straight-line assimilation theory. My research finds mixed evidence for the classic assimilation model. For example, native-born Mexicans are faring better than foreign-born counterparts in terms of English proficiency and educational attainment. However, in some cases I found no significant nativity differences in home ownership and unemployment rates. Furthermore, the process of social mobility and immigrant incorporation varies between the two cities. My findings suggest that geographic context has important implications for how contemporary immigrants and their offspring are faring in American society.

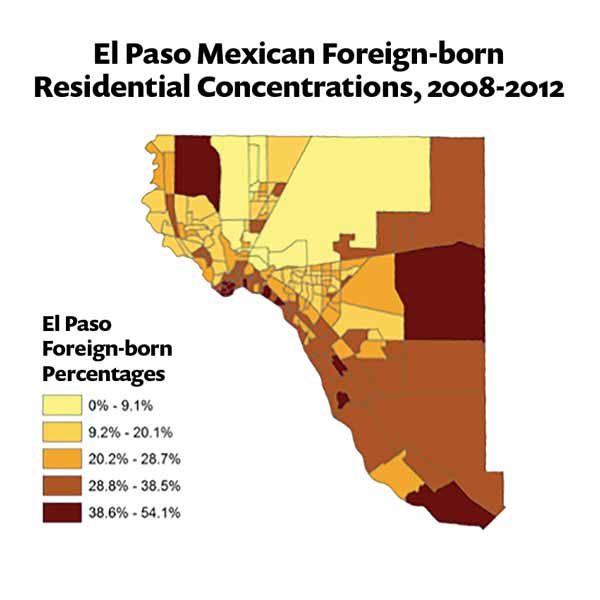

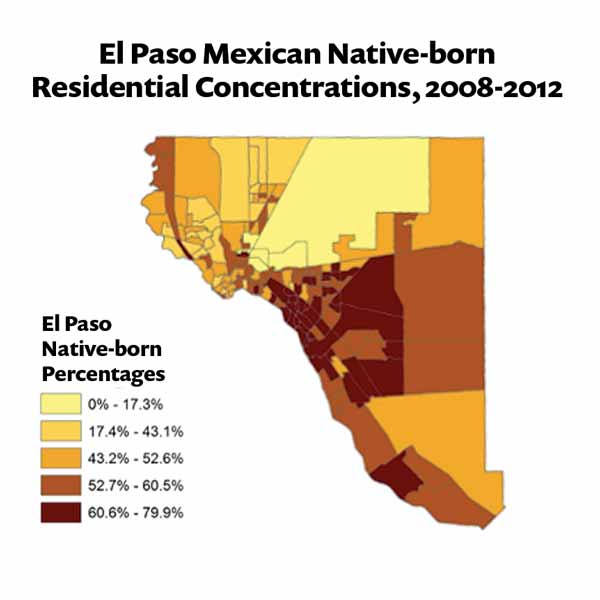

My study also incorporated Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to analyze residential patterns in both cities. I was interested in whether native-born Mexicans resided in neighborhoods outside of immigrant enclaves. Figures 1a and 1b illustrate the mobility being experienced in El Paso.

When analyzing San Diego, I found mixed results, leading me to conclude that integration process of Mexican immigrants varies from place and the context of reception. The maps I created for El Paso largely demonstrate that native-born Mexicans live in neighborhoods that are distinct from their immigrant counterparts. My maps for San Diego (not shown), however, reveal that immigrant and native-born Mexicans are living in similar neighborhoods. This finding suggests that context matters for residential mobility.

My re search experience has been the most rewarding time in my undergraduate career. I was able to meet like-minded individuals from various majors when I was invited to the Interdisciplinary Research Learning Community (IRLC) during the spring of 2015. These individuals reaffirmed the importance of asking questions. I am thankful for the opportunities and experiences I have gained from my research and look forward to continuing to do additional research. Without undergraduate opportunities such as these, many people like myself would not have been introduced to pre-graduate research programs.

search experience has been the most rewarding time in my undergraduate career. I was able to meet like-minded individuals from various majors when I was invited to the Interdisciplinary Research Learning Community (IRLC) during the spring of 2015. These individuals reaffirmed the importance of asking questions. I am thankful for the opportunities and experiences I have gained from my research and look forward to continuing to do additional research. Without undergraduate opportunities such as these, many people like myself would not have been introduced to pre-graduate research programs.